Due to dietary habits in the United States, despite eating too many calories many of us are deficient in vitamins A, C, D, and E and choline, calcium, magnesium, iron, and potassium. We are deficient in fiber. Our public health system promotes these nutrient deficiencies to encourage us toward better nutrition.

What do we do? More than half of us take vitamin supplements to ensure we don’t succumb to nutrient deficiencies that cause health problems. The most common reasons for consuming multivitamin and mineral supplements are to maintain or improve overall health, prevent health problems, and promote bone or heart health.

In truth, most of us are spending lots of money on supplements that may or may not be needed for our situation if they are even absorbed by the body. We’re guessing.

Couldn’t we get what we need from our diet?

It sure would be ideal. A careful person who consumes a variety of whole foods can approach the recommended daily allowances (RDAs) for most vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and other nutrients.

However, is the RDA right for you? It might not be:

- slight genetic differences in each of us change how efficiently our body uses various vitamins and minerals;

- the RDA is set based on the needs of healthy individuals; if you have a health situation, you likely need a different amount.

And, there is debate over whether synthetic nutrients provide the same benefits as natural nutrients. Some research even suggests that synthetic nutrients may be dangerous.

Is there really a difference, or is it just marketing nonsense? Let’s see what the literature has to say…

Whole foods and nutrient synergy

One reason why whole foods are better is, in large part, due to food synergy, or the beneficial relationship between food constituents. Nutrients interact with one another, some increasing the other’s effectiveness and others inhibiting it.

For example, eating avocado with your salad increases the bioavailability of the provitamin-A carotenoids in tomatoes and carrots. The phytochemicals in apples enhance the function of fruit antioxidants. Specifically, the even though a serving of fruit has only 5 mg of vitamin C, it is activated by phytochemicals to provide the equivalent of 1,500 mg of synthetic vitamin C in antioxidant activity. That’s right: if you look only at total vitamin C content, apples don’t measure up. BUT, when you look at activity they surpass the RDA because of the synergistic effects of phytochemicals.

Are synthetic nutrients biochemically identical?

Well… that is the accepted view, but what does that really mean?

Manufacturing synthetic nutrients is very different to the way plants, animals, or our deeply different human bodies create them. Despite having the same chemical formula, they are not identical. Your body may react differently to synthetic nutrients. It’s unclear how well synthetic nutrients are absorbed and used in the body. Some may be more easily absorbed, not others.

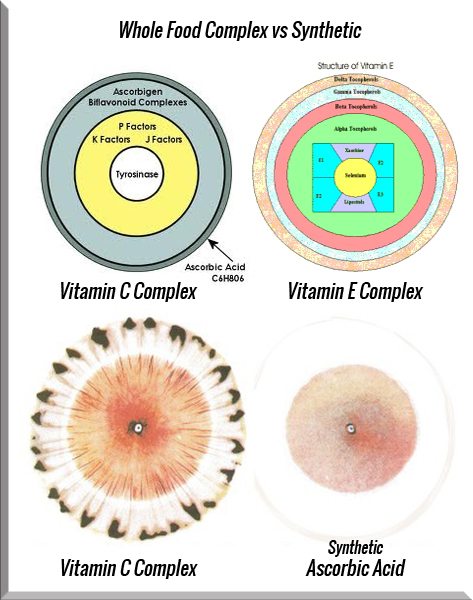

When you eat real food, you’re not consuming single nutrients, but rather a whole range of vitamins, minerals, co-factors and enzymes that allow for optimal use by the body. Whole foods supplements retain more of these co-factors. Look at the difference between the vitamin C complex from whole foods and the synthetic form from a test tube.

Without these additional compounds, synthetic nutrients are unlikely to be used by the body in the same way as their natural counterparts.

And how your unique body is genetically or epigenetically set up makes an enormous difference in deciding whether these synthetic counterparts are helpful or harmful. For example, high intakes of folic acid supplements may have negative health outcomes such as increasing the progression of precancerous lesions and tumors. This is even more problematic in individuals who have less efficient folic acid genetics.

For example, vitamin K and your bone health

Vitamin K is found in several forms in the human body. This K1 vitamin form is sent to the liver to make blood coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X (a deficiency in vitamin K slows clotting). The other forms (called the “long-chain mequinones” or MK) are used throughout the body.

Many of us take a calcium supplement for strong bones. Storing calcium in bones and maintaining blood calcium balance is a complex interplay of many factors, one of which is adequate levels of the MK forms of vitamin K. The MKs work synergistically with vitamin D; insufficient vitamin D and/or vitamin K as the MK forms will block bone mineralization no matter how much calcium is consumed—in fact, arterial calcification in vascular disease can become worse when there is an excess of calcium and insufficient vitamin K.

In food, the K1 form is notably found in spinach, kale, Brussels sprouts, and broccoli and some plant oils, and the long-chain menaquinones MK-7, MK-8, and MK-9 are present in fermented foods, notably properly aged cheese and natto and can also be made by strains of lactic acid bacteria in the human intestine. Vitamin K supplements have primarily the K1 form, although due to emerging understanding of the MK forms a few vendors have begun sourcing vitamin K from whole foods or lactic acid bacteria.

When comparing synthetic K1 supplements with food vitamin K sources (or whole-food-derived sources), the food-based forms elevate serum vitamin K faster and remain stable longer whereas the synthetic version is cleared more rapidly. While there are very few studies in people, animal models show similar absorption of minerals, vitamin K, and vitamin D regardless of source but much higher improvements in bone density when these are derived from whole foods.

Natural vs synthetic lycopene and heart disease

Lycopene, a carotenoid found in tomatoes, decreases risk of cardiovascular disease risk presumably through its strength as a powerful antioxidant. Of 17 studies testing isolated lycopene supplements compared with tomatoes or whole-food supplements (concentrated tomato skins where the lycopene is primarily found) 10 of the studies showed tomatoes to be effective in decreasing cholesterol oxidation (the understood cause of arterial plaque formation) and other markers of oxidative stress, while only 3 of the lycopene supplement studies showed any benefit—and the benefit measured was much smaller.

Several studies show both isolated lycopene and tomato products can effectively reduce inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein (CRP). Both supplements and tomato products show promise for reducing blood pressure. In the end, we need more information.

Half a kiwi or 50mg vitamin C?

A few animal studies demonstrate that natural vitamin C is absorbed better and more biologically active than its synthetic counterpart. But some do not. Interpret this with caution. In one notable study, a natural acerola cherry preparation ended up with almost no vitamin due to preparation methods.

In human studies, there is little difference in the urine and/or plasma levels of vitamin C whether from taking synthetic supplements or from fruits, fruit juices, and vegetables. That means it is being absorbed and eliminated equally well regardless of form.

Those studies tell you nothing about whether or not the synthetic C is functioning as well as the whole foods C.

Conclusion 1: We need more studies

There are many health benefits of eating whole foods or whole-food supplements that retain their synergistic nutrients. Intuitively, supplements made from whole foods are closer than synthetic versions to what the body evolved with all these eons. To date, while a few studies suggest this to be true, there is honestly limited evidence.

Conclusion 2: We need to understand our unique situation

There are times when you’ve tried everything you know. You’ve seen different experts, possibly taken a handful of pills, run numerous tests. This may have helped, but not enough.

The nutritional demands of disease are different from the demands of health. A body that is sick, overweight, has sludgy livers and poor digestion, is tired all the time, has accumulated too many toxic chemicals or metals… those place different demands on the body. In my practice, I use Nutrition Response Testing® to understand these needs.

My goal for my clients is to really listen to each person’s unique health situation, handle as much of it as possible by targeting diet. And use only carefully-selected supplements that are truly going to benefit the health situation—only for as long as they are needed.

Yours in health!

Blumberg, J. B., Bailey, R. L., Sesso, H. D., & Ulrich, C. M. (2018). The Evolving Role of Multivitamin/Multimineral Supplement Use among Adults in the Age of Personalized Nutrition. Nutrients, 10(2), 248.

Burton-Freeman, B. M., & Sesso, H. D. (2014). Whole Food versus Supplement: Comparing the Clinical Evidence of Tomato Intake and Lycopene Supplementation on Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Advances in Nutrition, 5(5), 457–485.

Boyer, J., & Liu, R. H. (2004). Apple phytochemicals and their health benefits. Nutrition Journal, 3, 5.

Jacobs, D. R., Gross, M. D., & Tapsell, L. C. (2009). Food synergy: an operational concept for understanding nutrition. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89(5), 1543S–1548S. http://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736B

Kantor, E. D., Rehm, C. D., Du, M., White, E., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2016). Trends in Dietary Supplement Use among US Adults From 1999–2012. JAMA, 316(14), 1464–1474.

Kopec, R. E., Cooperstone, J. L., Schweiggert, R. M., Young, G. S., Harrison, E. H., Francis, D. M., … Schwartz, S. J. (2014). Avocado Consumption Enhances Human Postprandial Provitamin A Absorption and Conversion from a Novel High–β-Carotene Tomato Sauce and from Carrots. The Journal of Nutrition, 144(8), 1158–1166.

Schurgers, Leon J., Teunissen, Kirsten J. F., Hamulyák, Karly, Knapen, Marjo H. J., Vik, Hogne, & Vermeer, Cees. (2007). Vitamin K–containing dietary supplements: comparison of synthetic vitamin K<sub>1</sub> and natto-derived menaquinone-7. Blood, 109(8), 3279-3283.

Van Ballegooijen, A. J., Pilz, S., Tomaschitz, A., Grübler, M. R., & Verheyen, N. (2017). The Synergistic Interplay between Vitamins D and K for Bone and Cardiovascular Health: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Endocrinology, 2017, 7454376.

Yetley, E. A. (2007) Multivitamin and multimineral dietary supplements: definitions, characterization, bioavailability, and drug interactions. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 85(1): 269S-276S

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.